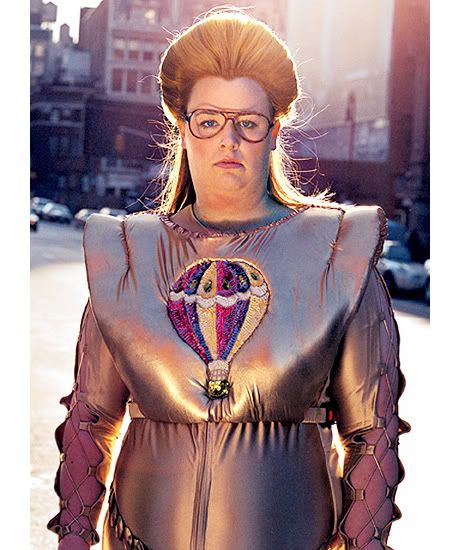

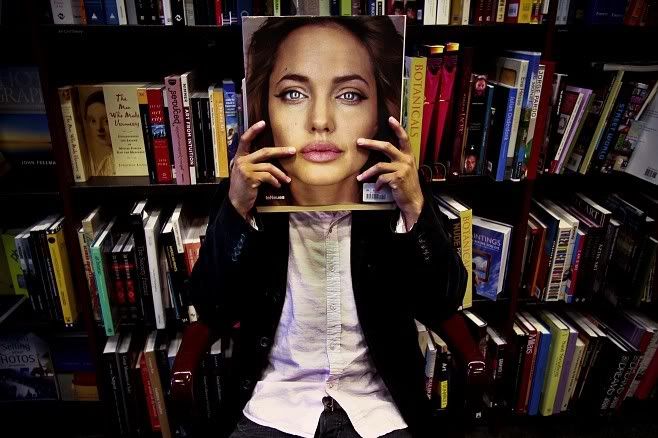

Photo by Chloe Scheffe

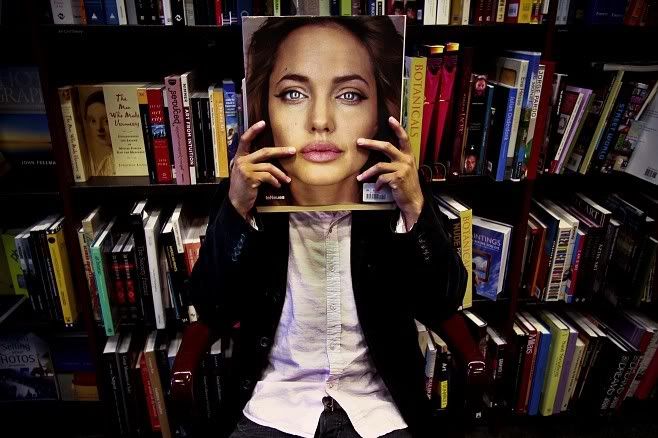

Chuck Klosterman uses words like abject, schism and ungulate. I sulkily admit I had to look up their meanings. Reading a half hour of Chuck Klosterman's disquisitional essays in

A Decade Of Curious People and Dangerous Ideas is mind-blowing on this level. I assume a well-thumbed thesaurus is always with him; but I have no proof beyond his particular, intellectual and varied, speech staccato peppering all his work. I'm in awe, but not in love.

I'm alone in my lovelessness - there are those who are head over heels: two friends of mine are crushing on Chuck because, as Lauren Salazar from

Daily Intel put it, he's got a 'nerdy hotness' about him that makes you sympathize with his wistful fictional characters (he says that "No one ever has sex in his books because he identifies more with people being rejected") and quirky personal real-life stories. Just select a piece from

Sex, Drugs and Cocoa Puffs, a running commentary on pop culture and its icons - an extension of his comprehensive work - and you'll find a man colored by hilarious juvenile tales and a keen awareness of how to translate what happens around him into a contextualized concept.

When asked if he had a critical aesthetic, which sounds to me like a question about his particular brand of presentation, he says, "I don't know that I have an aesthetic, really. If I do, it would be that I think there are people who want to think critically about the art that engages their life, and I think you can do that with any kind of art. There's this belief that some things can be taken seriously in an intellectual way, while some things are only entertainment or only a commodity. Or there's some kind of critical consensus that some things are "good," and some things are garbage, throwaway culture. And I think the difference between them, in a lot of ways, is actually much less than people think. Especially when you get down to how they affect the audience. So when I write, I don't think it necessarily matters what I'm writing about. I think it matters the way I think about it. The chord changes, and the lyrics on a record have value, but their real value is how they shape the way people look at their own lives."

Although Chuck states that no one can really write an objective piece because it's based on the author's "subjective objectivity," he nevertheless strikes a chord with partakers of pop culture; I think that chord is a collective sense of cynism. In his own words, "I think there's an element of cynicism in my writing, but I'm an optimistic cynic."

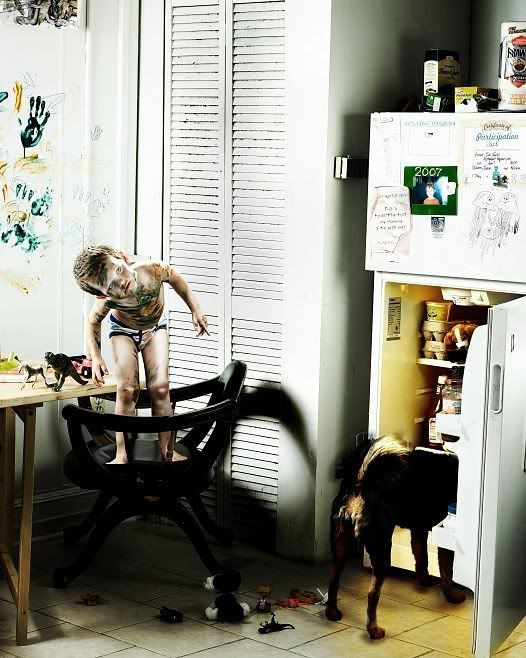

Photo by Ellen Choi